At the beginning of Franz Kafka’s In the Penal Colony, a condemned man on an island prison lies tethered to a strange machine. Referred to as, the “Apparatus”, Kafka’s machine is made up of three parts: the human-shaped “Bed”, in which the prisoner is strapped; the “Harrow”, lined with needles which inscribe on their body over a period of twelve hours the law which the condemned person has violated; and the “Inscriber”, which determines the movement of the Harrow. This man we learn, will have inscribed on his body, ‘Honour your superiors.’

Completed one-hundred years ago this year, Franz Kafka’s In the Penal Colony can be read as a metaphor for the Ideological State Apparatus and the tools invented by humans to exert control over others. Society, fuelled by the human drive to power, is designed for the subjugation and exclusion of minorities; the representation, or construction, of majority and minority identities within any given society being controlled by the group that has the greatest political power. As a cog in the Apparatus of power which produces this “Otherness”, representation–the system of language, signs and images which represent things–is an essential part of the process by which power is produced and enforced upon members of a culture.

To use a phrase coined by the French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in relation to Kafka’s writing, Anthony White’s Signs of Civilisation offers a “line of escape”1 from this Apparatus. In White’s socially engaged practice, non-representational abstraction offers “a way out” through embracing the Otherness of the non-image; a line of enquiry and mode of working which has dominated his practice since emigrating to France from Australia eight years ago.

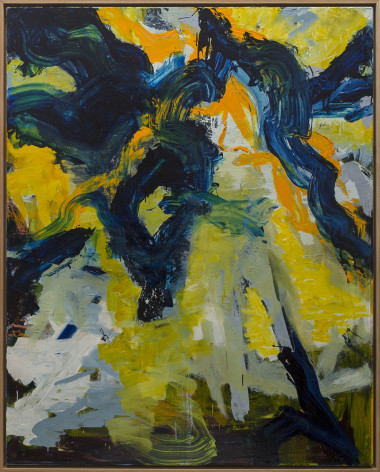

This personal experience extends into White’s consideration of state power, particularly in relation to global immigration crises. Signs of Civilisation takes Kafka’s In the Penal Colony as a starting point for a series of intensely visceral paintings which consider the political role of art in contemporary society. In The Apparatus I, the inhumane effects of social homogenization are empathetically enacted on the image through the movement of a squeegee as it passes over wet oil paint, slowly erasing detail to create an almost uniform assimilated surface. The action is interrupted. The resulting image rests in that precarious state between erasure and becoming. In New Colossus, the canvas is encrusted with scumbled blood-red pigment, like an old congealed wound reopened.

The ethics of aesthetics has been an ongoing concern for White. Having recently returned from a residency at the Mark Rothko Centre in Latvia, his most recent work stems from an examination of Rothko’s interest in the capacity of non-objectivity to express a sense of self-awareness through the interrogation of tragedy, ecstasy and doom; extending non-objective painting beyond mere colour relationships: “If you are only moved by colour relationships” Rothko says, “then you miss the point.”2

The point is, as Rothko’s teacher Josef Albers put it, colour is relative, volatile and political.3 Even the most abstract looking art, Albers says, has, if your eyes are open to it, everything to do with life.4 Kafka was one of the modern writers most admired by Rothko.5 His thinking resonates with the underlying theme of Otherness in much of Kafka’s writing: “You are not from the Castle” says the landlady in Kafka’s 1926 novel, “you are not from the village, you aren’t anything, or rather, you are something, a stranger.”6

Kafka and Rothko come together in Anthony White’s, Signs of Civlisation. The exhibition’s message of art as agency is especially pertinent today, in a world where tens-of-thousands of people have lost their lives seeking asylum from war, violent totalitarian regimes or religious persecution; a world in which Kafka’s Apparatus is mirrored in the destructive immigration policies of powerful countries like Australia and America. In the Pacific, Australia’s solution to this humanitarian disaster has been to build prisons; mandatory detention centres on Manus Island in northern Papua New Guinea and at Nauru, a small island nation in Micronesia. In the United States, the words New Colossus, have taken on an entirely different meaning from the welcoming declaration penned by Emma Lazarus in 1883. The new populist “brazen giant” now attacks the “huddled masses” with false truths and fundamentally discriminatory executive orders which shatter all definitions of liberty and democracy.

Truth is represented by Kafka as a break, a flaw in the system, a possible way out. Presented at a time of global humanitarian crises, Signs of Civlisation proposes a way forward through engagement, political awareness and social responsibility. Anthony White reminds us that artists (indeed all citizens) have a responsibility to participate in social and political actions, and that the use of cultural items as expressions of these actions beyond mere decoration, is what really makes a civilisation progressive. In this way White’s practice is borne out of a lineage of generations of painters for whom colour and the gestural brushstroke communicated a certain type of freedom. White employs the painterly gesture as a tool to consider the possibilities of that freedom today.

Signs of Civlisation speaks to the complexity of our lives and our humanity. It speaks to our social obligation, to our social contract with one another. White’s insistence on the ethics of aesthetics, positions his work not among the isolated phenomena of Clement Greenberg’s “abstract expressionism,” but within the scope of Harold Rosenberg’s idea of an “action painting” with which to investigate the world; not a picture but an “event”. This methodology–far from placing the aesthetic elements of the picture plane above the everyday world like so much formalist abstraction–actually compresses the two, creating a useful and powerful cultural artefact.

Mirroring the function of Kafka’s Apparatus, White’s visual language of slashes, splatters, smears and scars constructs a “text” which describes to us our sentence as viewers. If we could read it, it might sound something like these words spoke by the great Caree Mae Weems: “If I am deeply aware of my humanity then I must be aware of yours. That’s the thing that binds us. Its the social contract that exists between us.

Robert Maconachie, Sydney February 2018

A moral code based on the social.”

1 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, “Kafka:Toward a Minor Literature”, Theory and history of literature; v. 30, University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, London, 1986, p.6

2 Mark Rothko quoted in Selden Rodman, Conversations with artists, Devin-Adair Co., 1957, p.94

3 Holland Cotter, “The science and the Soul of Seeing”, The New York Times, 01.12.2016

4 ibid.

5 David Anfam, Mark Rothko: The Works on Canvas : Catalogue Raisonné, Volume I, p.12

6 James E. B. Breslin, Mark Rothko: A Biography, p.31.