Leslie Rice

“At the time of writing, tan lines are cool. By the time you read this, they may not be. So it is with fashion. In the nineteenth century, a suntan was a mark of low social class, as most labour took place outdoors; untouched porcelain skin was a sign of privilege. Like colonialism and kitsch, the prestige associated with being pasty white was heavily impacted by the industrial revolution. Around the 1920s, the script was flipped—the humble tan came to be a sign of the free and easy leisure of the well-to-do; to be pale an indicator that one must work indoors during daylight hours. A brief sun-smart inversion in the 1990s saw clever people chalky again, only for Gen Z to embrace the twenty-first-century social media trend of cunningly and strategically tanning their white bodies in all manner of shapes and patterns.

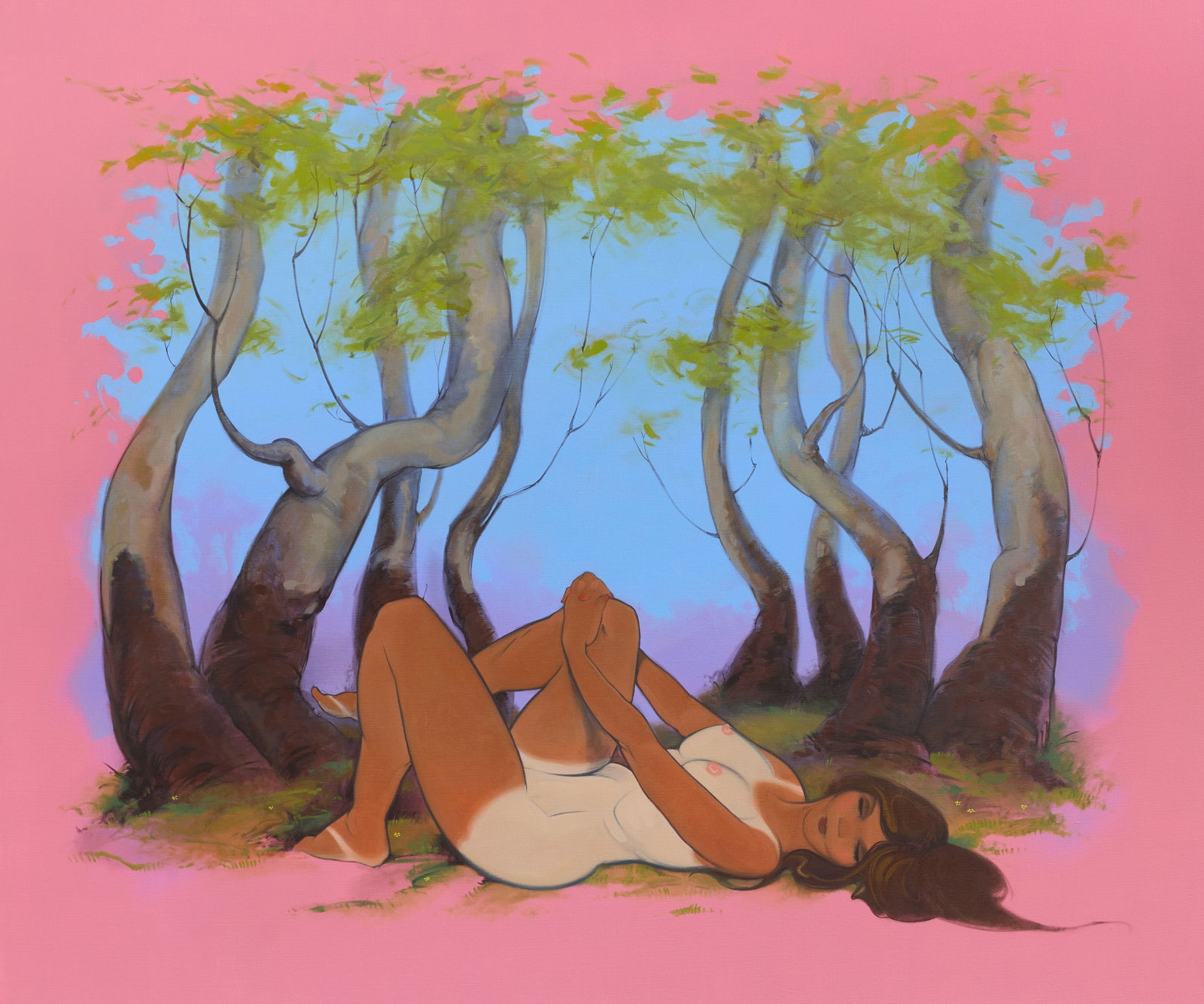

Our Olympia of Rooty Hill bears a suntan that reveals her own confusion and internal struggle with the idea of class. She is at once as sunburnt as the wide brown land that she loves, and as white as any Australia Policy since Federation. Her persistent choice of Chesty Bonds singlet, Ruggers footy shorts, and flip-flop thongs has somewhat indelibly marked her, revealing her proclivity for working-class attire even when naked.

When Manet painted his Olympia in 1863, it caused a stir with its frank depiction of female nakedness—not nudity, but nakedness. Her state of being unclothed in a raw, unidealised, and potentially vulnerable way, with slippers on her feet and a choker around her neck, grounds her in the real world and draws attention to the physical reality of her state of undress. By way of contrast, Titian’s Venus of Urbino, from which Manet drew inspiration, presented the reclining female body as an idealised, mythological form—a nude in the classical sense.

Our Olympia of Rooty Hill is naked, wearing nothing but a smile and the mark of her class.”