Tom Adair’s New Romantics recontextualizes iconic romantic paintings of the Australian land-scape by expanding their resonance into our technologic era. By merging familiar internet mo-tifs with historic homages to nature, New Romantics at once looks forward and back in time, questioning the relationship between beauty and value.

This major collection furthers Adair’s signature chromatone application of airbrush on both in-timate and grand scale, alongside mirrored aluminium and neon lighting, three contemporary mediums that transport historical aesthetic values into the future. Core to New Romantics is Adair’s view that nature and human nature are inseparable, even in the age of the iPhone.

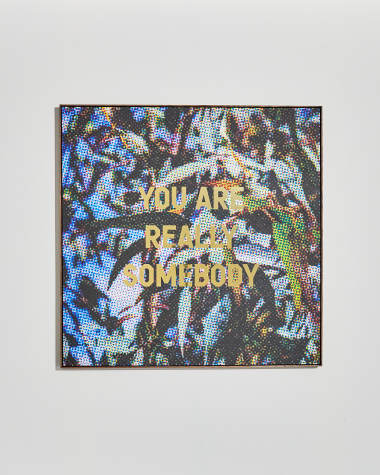

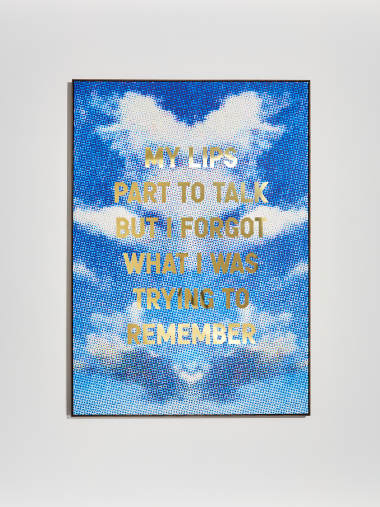

Adair explores the evolution of the human gaze by altering the viewing framework of subjects from art history in order to mimic the contemporary eye. Where John Glover’s The Bath of Diana, Van Diemen’s Land idealizes the textural gum trees of the native Tasmanian wilderness, Adair digitally crops, replicates and transforms a graft to produce a work of greater stature than the original; self-reflection and hyper-curation are intrinsic to remade form. In titling this work The Story of Diana’s Bath, Adair alludes to the self-promotion of social media imagery taken in baths, and extends this textual focus more directly in Really Tho through the golden block text “YOU ARE REALLY SOMEBODY” and Whisper in the Clouds, which reads “TWEET NOTHINGS.” This use of phrase as subject continues the developments of artists like Ed Ruscha, while echoing high fashion, such as Louis Vuitton’s The Masters Collection, which itself appropriates art with text. Whether the text floats in front of clouds or flora, the textural contrast mirrors a dichotomy between nature and human nature, without advocating either as a primary subject. Suggestions of computerized manipulation and upload clouds affirm the omnipresence of technology.

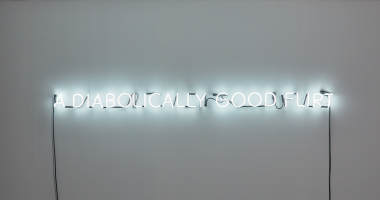

Textual aphorisms are stamped throughout New Romantics, imbuing the works with the self-reflective vanity of our time, as well as an undercurrent of critical humour. The wall-mounted work Courting, a simple pink neon caption reading “SEND NUDES,” implies both sent and received communications, a base intent, titillating invitations, and public excoriations, all at once; the seductive soundbyte also illuminates the massive change in ethos from early nineteenth century Romanticism to the romantic arena of today with its sexual freedoms, enhanced by machines and apps.

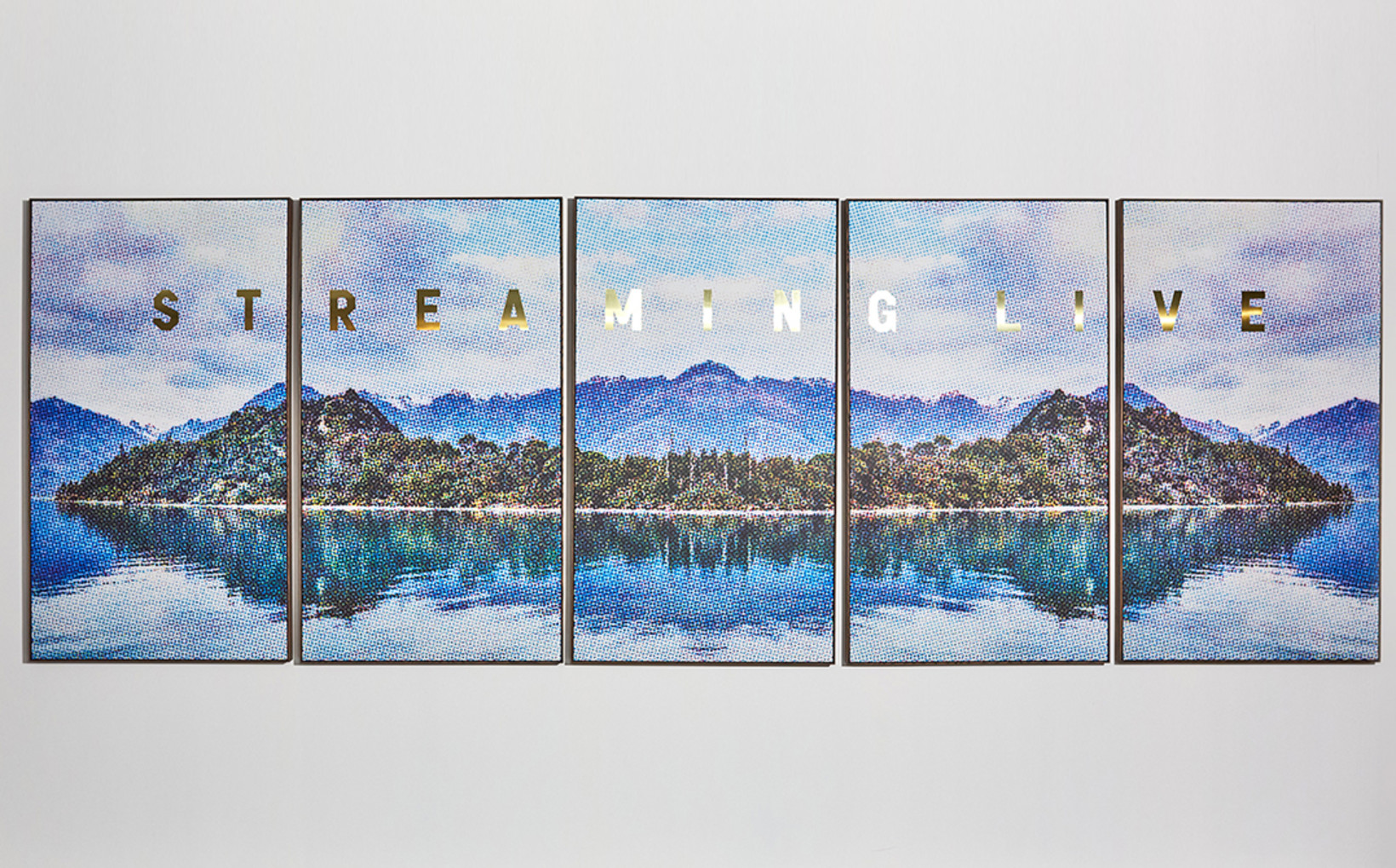

Across five wall-length vertical panels which each mimic the ratio of iPhone screens, the large-scale painting 24/7 emits sheer natural majesty, wrapping the viewer in the grandeur of Lake Wakatipu through the foundational elements of water, rock and sky. Like an omnipotent presence, “STREAMING LIVE” hovers, layered in overt meaning. But this vast panoramic view is in-terrupted by vertical framing, another formal nod to technology and its scope; instead of limiting the image, such framing brings speed to the scene through rhythm. The viewer might recall the swooping Paramount film production house video sequence, and all its connotations of fictional largess.

Importantly, the mountain’s horizontal reflection in the lake is itself reflected vertically by digital manipulations of symmetry, a recurring motif of New Romantics which highlights two types of touch held in Adair’s human hand; the first adds artificiality to nature by mirroring, but the second is a softer, more organic sensibility, which undoes the mathematic reflection by applying dot after dot, with great care, in organic but controlled positions. This second type of touch undoes the perfectly symmetry of the image. Regional nuances of colour blossom from this human attention, which can be admired in Down the Rabbit Hole, based on Eugene von Guérard’s North-East View from the Northern Top of Mount Kosciusko. Adair chops and reflects nature, only to return it to the organic realm.

There is much pleasure in seeing Adair’s craft up close, nose-to-paint, where each cell of air-propelled colour claims its own territory all the while blurring and blending with competing cells. These disks carry an aesthetic both alien and fundamental to Adair’s final images. That these paintings capture so many dimensions of human nature in only four colours is itself a startling reflection on beauty.

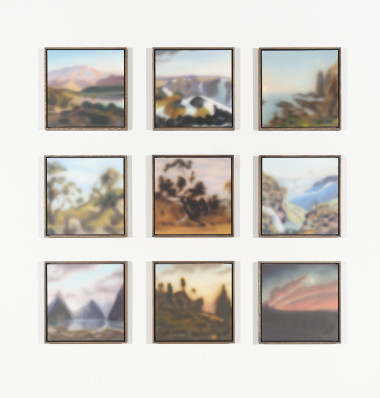

Through fifteen smaller works, Adair evolves his technical approach to airbrush by using more colours, achieving a dreamlike focuslessness. This haze faithfully reproduces the sentimentality of Romanticism, though the swooning effect is subverted by the grid mode display, borrowed from Instagram, which invites the viewer to ponder the transience of sentimentality, and how such images are milled for popularity and esteem through followers and likes.

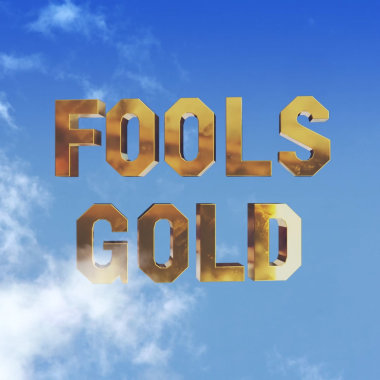

Three NFTs take Adair’s textuality into the cryptoverse, a new arena embedded with intrinsic questions of value, reflected in phrases like “FOOLS GOLD.” The golden gleam of the 3D lettering is carefully textured, as if fingerprints had grasped them out of want, and complements the pristine golden elements of the physical paintings, where text functions as framing too. Because these framing devices are mirrored, they include the audience, who must see themselves through the work, among language reminiscent of internet memes and the never ending stream of internet information. The world of technology contains the complex beauty of human nature, through Adair’s eyes.

While creating New Romantics, Adair chose to abstain from social media. This momentary escape from the digital realm confirmed Adair’s reverence for the value of the natural world.

Mark Chu

December, 2021