Myth: Group Exhibition

-

-

Myth is a dialogue between the stories that make us. The powerful narratives collapse distinctions between time and space in a complex interrogation of cultural heritage.

-

Ralph Hobbs

AUGUST, 2020

Historical explanations and cautionary tales – myths – conjure meanings that are powerful and insightful. Generationally, they inform and direct the path forward for our society and culture. In this land, we see the stories of the ancients – the Greek and Roman tales of old that were imagined and reimagined in marble and paint—forming the foundations of the Western tradition of art-making in this country. These perspectives are juxtaposed with the eternal longing of the First Nations peoples—their Tjukurrpa (Dreaming) is old and it remains ever strong. These stories have survived and have had much to tell us about how to live.

Myth is a dialogue between the stories that make us. The powerful narratives collapse distinctions between time and space in a complex interrogation of cultural heritage. The positioning of the exhibited artworks invites an investigation into the controversial and conflicting perspectives that shape our collective history.

Myth provides us with an array of intoxicating conversations. Blak Douglas’ He’s Only Half the Man He’s Made Out to Be (2018) hangs beside Arthur Boyd’s Bridegroom Drinking From a Creek (1959). The paintings are powerful in their direct and viscous imagery—their colour and form unique to the artists’ oeuvre. Their personal experiences and observations are distilled and representative of their time. They speak of the marginalisation of the First Nations peoples and the effect that the purgatory of colonisation has had on the ancestors of the land. The dialogue between the two paintings created 59 years apart is poignant and profoundly relevant in a contemporary society that seeks a solution for the inadequacies of the past.

In a serendipitous moment, the raw songlines of George Hairbrush Tjungari—a direct image from the time of creation—speak a similar eerie language to the lines that flow over the epic desert landscape of John Olsen’s Flight Over the Kimberley (1997). The artists seek to capture the essence of the life force of this land. It’s not God they seek but some power that is explained and is inherent in the imaging of the landscape of their mind—anchored by their own stories and personal guiding mythology.

Dee Smart’s Fragmented Leap of Faith (2020) draws both visual and allegorical parallels with Sidney Nolan’s Leda and Swan (1960). Smart’s dancing swan, Ella Havelka—the Australian Ballet’s first Indigenous dancer—hints at the generational empowerment in the paradigm of high Western art. The palpable connection to Nolan’s ancient story of passion reminds us of the philosophical power of the ancients. Jonathan Dalton’s nod to Poseidon captured deep in the lens of a drowned camera, along with the artist's customary wit, reminds us of the enduring legacy of the visual image in the formation of our history.

The tyranny of distance and its ensuing isolation permeates Sidney Nolan’s Sandhills Near Birdsville (1953) and is echoed in Jason Benjamin’s wistful, enigmatic, big sky landscape. Benjamin reminds us that isolation is not only a geographical affliction; it is a truism of which we are constantly reminded in the time of COVID. Delving into the natural symbolism of lone trees and distant horizons, the artists illustrate the melancholic longing that is a recurring theme in the Australian psyche.

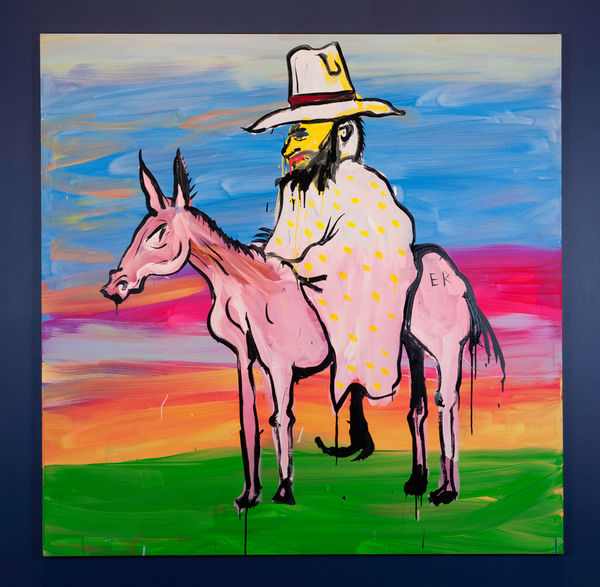

There is no greater legend in Australia than that of Ned Kelly—Australia’s most famous of rogues—immortalised in the paintings of Nolan. It was a theme that he revisited throughout his life from the 1940s. Nolan’s Kelly Head (1947) is a rare unmasked painting of Kelly. The flat enamel treatment of Ned Kelly’s eyes provides its own mask, luring viewers into Ned Kelly’s menacing world. Gria Shead reminds us that mythology can be used as a tool to marginalise. Shead’s haunted painting of Kate—Ned Kelly’s sister ostensibly written out of history—appears through the desolate landscape, acting as a powerful reminder of the inequities of the past. Adam Cullen—an outsider himself—brilliantly recontextualised the idea of Ned Kelly in the late 2000s. Part Spaghetti Western, part Camp/Pop hero of the oppressed, Cullen’s chaotic execution is undeniably engaging in its reconstruction of the Kelly myth.

Both Nolan and Cullen paved the way for the every day to become elevated. James Drinkwater’s poignant works depict both the firefighter and the boxer—characters deeply embedded in his family mythology. Through the darkened palette and the bronze patina, there is hope. Extraordinary lives have been an enduring theme in the creation of our myths.

A collective acknowledgement and sharing of our mythology is the underpinning of a stable society. History tells us that the passing down of stories and enduring messages allows for cross-cultural ideas of hope, joy and memory. An understanding of past and present stories can provide a flaming torch in the darkness of a world in flux.

-

Works

-

Adam CullenKelly on His Horse, 2009Acrylic on canvas183 x 183cmSold

Adam CullenKelly on His Horse, 2009Acrylic on canvas183 x 183cmSold -

Arthur BoydBridegroom Drinking From A Creek, 1959Tempera and Oil on boardF. 98 x 135cm

Arthur BoydBridegroom Drinking From A Creek, 1959Tempera and Oil on boardF. 98 x 135cm -

Arthur BoydLovers, 1962Oil on boardF 137 x 197.5cm

Arthur BoydLovers, 1962Oil on boardF 137 x 197.5cm -

-

George Hairbrush TjungurrayiUntitled, 2009Synthetic polymer paint on linen153 x 183cmSold

George Hairbrush TjungurrayiUntitled, 2009Synthetic polymer paint on linen153 x 183cmSold -

-

-

-

Jason BenjaminUntitled, 2020Oil on primed handmade paperF. 60 x 79.5cmSold

Jason BenjaminUntitled, 2020Oil on primed handmade paperF. 60 x 79.5cmSold -

Jason BenjaminWe're all on the long road, 2020Oil on primed handmade paperF. 60 x 79.5cmSold

Jason BenjaminWe're all on the long road, 2020Oil on primed handmade paperF. 60 x 79.5cmSold -

Jonathan DaltonTwo Japanese Tourists visit Poseidon of Melos, 2020Oil on linen137 x 121cmSold

Jonathan DaltonTwo Japanese Tourists visit Poseidon of Melos, 2020Oil on linen137 x 121cmSold -

-

John OlsenLake Eyre, 1997Oil on linenF. 198 x 198cmSold

John OlsenLake Eyre, 1997Oil on linenF. 198 x 198cmSold -

Nyurapayia NampitjinpaUntitled AEMRSB200939-JJC59SY, -Acrylic on linen122 x 305cmSold

Nyurapayia NampitjinpaUntitled AEMRSB200939-JJC59SY, -Acrylic on linen122 x 305cmSold -

-

Sidney NolanKelly Head, 1947Enamel on boardF. 95.5 x 83cmSold

Sidney NolanKelly Head, 1947Enamel on boardF. 95.5 x 83cmSold -

Sidney NolanLeda and the Swan, 1960Ripolin and enamel on boardF. 98 x 128.5cmSold

Sidney NolanLeda and the Swan, 1960Ripolin and enamel on boardF. 98 x 128.5cmSold -

-

Blak DouglasHe's Only Half the Man He's Made Out to Be, 2018Synthetic polymer paint on canvas130 x 105cmSold

Blak DouglasHe's Only Half the Man He's Made Out to Be, 2018Synthetic polymer paint on canvas130 x 105cmSold -

-

Wentja NapaltjarriRockholes west of kintore AEWMN001347PAGAcrylic on linen120 x 120cmSold

Wentja NapaltjarriRockholes west of kintore AEWMN001347PAGAcrylic on linen120 x 120cmSold -

James DrinkwaterThe Firefighter, 2020Oil on CanvasF. 89 x 78.6cmSold

James DrinkwaterThe Firefighter, 2020Oil on CanvasF. 89 x 78.6cmSold

-

-

Video