The sound of a crying baby had ricocheted through the dusty streets of the remote community of Mount Liebig all day, and all the night before. It's a small, remote township in the Western Desert of Australia, populated by about one hundred and sixty Pintupi and Luritja people. The community nurse couldn’t quell the anguish of the little girl. At her wit's end, her mother had walked to the local art centre. Inside, Bill Whiskey Tjapaltjarri sat working on one of his vast paintings. It was a work imbued with his stories, ancient history, and lore—a different sort of history to the written one we are familiar with.

He looked up and held out his arms, and the mother gave the baby to him. He put his hand on her forehead and began to sing a story from another time in language. Almost immediately, the little girl's cries stopped—Bill passed her back and returned to his painting. The old man was a Ngangkari, a healer. Throughout the red desert, people would say he had ‘panpura ngangkarinanyi’ or ‘someone who could touch the soul’. Bill lived in this world, but his power was from another.

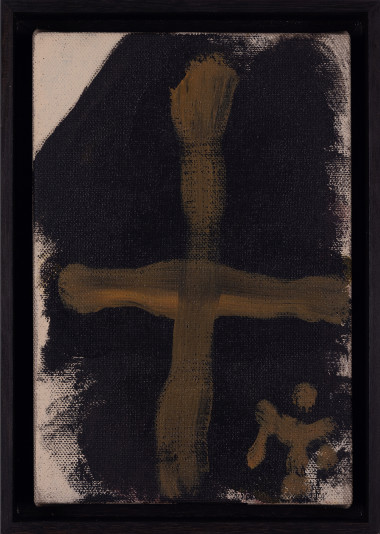

It’s hard to rationally explain the events of that day. However, the essence of what we can’t begin to understand is attuned to the heart of this exhibition. In the old man’s paintings, the lore lives on. The lines and dots—these hidden narratives—show us an alternate way of connecting with the land, each other, and our subconscious.

—

In Other Worlds, old and new worlds converge. History painting and personal narratives intersect. The Edge, by Peter Gardiner, draws from the 1857 painting Niagara by Frederic Edwin Church. It is a work with a Divine quality, the sense of awe is enough to send one into palpitations upon viewing. The power of the water plummeting over the edge contrasts with a strange sense of calmness in the face of calamity, unified through the colour that floods the picture.

Gardiner’s articulation is juxtaposed with Brett McMahon's gothic, introspective investigations of the Australian bush—vast, yet magnified through a narrow aperture. The sense of entanglement in the landscape is all-pervasive. The artist is in tune with his observations of his world. He transfers our consciousness to another place. The texture of old broken trees and fire-blackened surfaces has a physical materiality that envelops us, and yet we cannot look away.

Matt Coyle’s Vestibule is a deeply beautiful yet disturbing vision of comfort. The seductiveness of the painted surface suggests a comfortable sitdown could be transported into the dark heart of a David Lynch film. The illusory experience reminds us that beauty and dystopia can collide, and we must seek truth beyond the obvious.

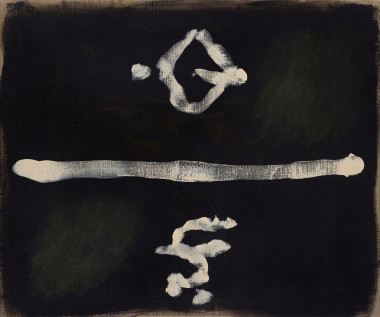

Lottie Consalvo's video work, La Femme, is a deep meditation. Raw, yet hypnotically beautiful, it blurs the lines between ritualistic and subliminal languages. The deeply moving sentiment within the video is echoed within her paintings. Part abstraction, part literal experience—it is transcendent. Consalvo delivers all in a deliberately ambiguous language, and we are challenged to decipher if this is the past, or the present.

The way we acknowledge our place in the land and the historical truth of our heritages is under constant interpretation and revision. It is the role of the artist to forge narratives that make us think beyond what our eyes would have us believe. Look again at the painting by Bill Whiskey Tjapaltjarri. The only linkage to the magic he possessed is embedded in the canvas.

Ralph Hobbs

September, 2024