Landscape And Memory: Group Exhibition

-

-

Throughout history and across cultures, the idea of the landscape genre has served many masters. The connection of place to our history cannot be underestimated. In Australia, artists have used the landscape for many reasons beyond the picturesque imaging of the natural beauty of this land.

-

Ralph Hobbs

AUGUST, 2023

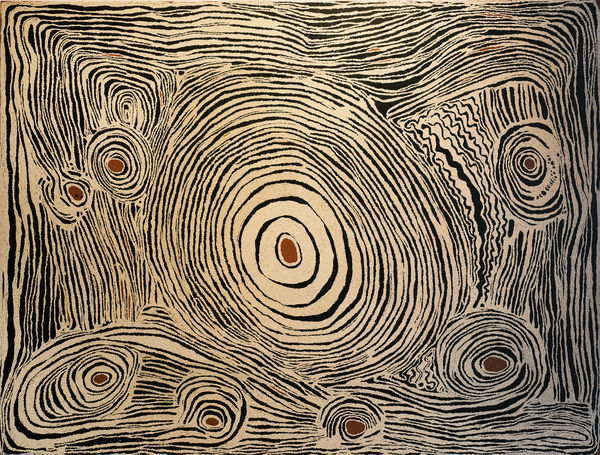

Nyurapayia Nampitjinpa, aka Mrs Bennett, was a complex woman—holder of all knowledge and law in the vast area around the rockhole system she called Punkilpirri—a hidden valley in the Peterman Ranges of the Western Desert of Australia. It is a beautifully precarious place where life-giving water is permanent and, for this grand old woman of the desert country, a spiritual home.

Nyurapayia was not one to suffer fools, yet she was always enthusiastic to explain the beauty and importance of where she once lived. The ancient stories of her Tjukurrpa were an ever-present narrative— her connection to country—the landscape of her mind was her reason for living. Her culture has remained alive and strong through her painting, singing, and storytelling. All of these were integral to life in the desert—the clues to existence are intrinsic in the paintings, and her memories of living there were forever etched in her heart. It is a gift to a Nation that is wrestling with its identity. The painting reminds us that whoever we ultimately believe we are, the fundamental fact is we exist in this ancient land, and our collective future culture is embedded in it.

Throughout history and across cultures, the idea of the landscape genre has served many masters. The connection of place to our history cannot be underestimated. In Australia, artists have used the landscape for many reasons beyond the picturesque imaging of the natural beauty of this land. Artists have always composed images to tell stories of the past and present. In the past, the genre has been used as an agent of colonisation; in effect, painting the landscape was a way of ideologically possessing a place. In recent decades, there has been an irrefutable acknowledgement of traditional ownership of this land due in no small part to how First Nation artists have imaged the landscape.

For artists with a non-Indigenous heritage, the stories of this place invariably have a subliminal connection to other countries and cultures. Their narratives manifest from literal to abstract; the memory of place makes these moments so powerful. This exhibition has drawn on paintings from diverse influences, backgrounds, and times.

The work of contemporary artists Peter Gardiner and Nicolas Blowers—painters who navigate the visual vocabulary of the European landscape tradition—construct their paintings from the memory of places. Often broken yet still beautiful they remind us of the fragility of our environment. Stephanie Eather’s abstraction of a working sheep station is a meditation that acknowledges the landscape as a metaphor for something other than the literal. The sensuousness of Brett Whiteley’s drawn line is an evocative reminder of the human form we manifest when viewing the land. The monumentalism of Suzanne Archer’s paintings is born from her exploration of the landscape she holds dear.

Her work has an ethereal sensitivity, balancing the known and imagined composition. The rambunctiousness of Adam Cullen’s Kelly at Glenrowan—the mythical figure that looms large from Australian bush folk law is contextualised in all its Post Pop/Punk innuendo. It is a work that reminds us of the stories from the past that continue to ricochet around our contemporary consciousness.

Ultimately, the exhibition explores the exquisite intangibility of retrospection. What we have experienced, where we live, and who we are, whilst anchoring the narrative in the context of our landscape. It seeks to point to the realisation that we collectively are better able to navigate the future of our country through cognitively acknowledging our existence in it.

-

Works

-

-

Suzanne ArcherUnderflow, 2022Oil on canvas213 x 366cmSold

Suzanne ArcherUnderflow, 2022Oil on canvas213 x 366cmSold -

Nicholas BlowersChalk Pit Hollows, Devils Drop, 2023Oil on canvas, framed165 x 189cmSold

Nicholas BlowersChalk Pit Hollows, Devils Drop, 2023Oil on canvas, framed165 x 189cmSold -

Nicholas BlowersStudy for a wood in rose madder crimson, 2023Oil on canvas, framed59.5x82.5cmSold

Nicholas BlowersStudy for a wood in rose madder crimson, 2023Oil on canvas, framed59.5x82.5cmSold -

Nicholas BlowersStudy for a wood in violet, 2023Oil on canvas, framed59.5x82.5cmSold

Nicholas BlowersStudy for a wood in violet, 2023Oil on canvas, framed59.5x82.5cmSold -

-

James DrinkwaterThe Magnificent life of Nevia Consalvo, 2019Oil on canvas, framed216 x 165cmSold

James DrinkwaterThe Magnificent life of Nevia Consalvo, 2019Oil on canvas, framed216 x 165cmSold -

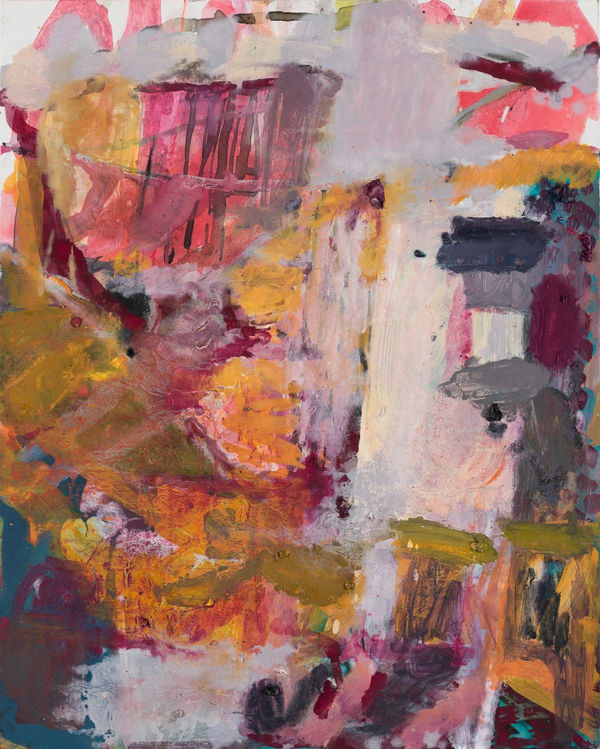

Stephanie EatherFreshly cut grass and hot pink socks hanging on the hills hoist outside the homestead, 2023Oil on polycotton, framed (FX frame)77cm x 61cmSold

Stephanie EatherFreshly cut grass and hot pink socks hanging on the hills hoist outside the homestead, 2023Oil on polycotton, framed (FX frame)77cm x 61cmSold -

Peter GardinerWhirlpool Study, 2023Oil on board40 x 30cmSold

Peter GardinerWhirlpool Study, 2023Oil on board40 x 30cmSold -

Peter GardinerPortarlington, 2023Oil on board30 x 40cm

Peter GardinerPortarlington, 2023Oil on board30 x 40cm -

Peter GardinerEmber Study, 2023Oil on board30 x 22.5cmSold

Peter GardinerEmber Study, 2023Oil on board30 x 22.5cmSold -

Peter GardinerStill Life 36, 2023Oil on paper, framed (FX frame)37.5 x 29.5cmSold

Peter GardinerStill Life 36, 2023Oil on paper, framed (FX frame)37.5 x 29.5cmSold -

Peter GardinerApotheosis V, 2023Oil on board120 x 90cmSold

Peter GardinerApotheosis V, 2023Oil on board120 x 90cmSold -

Peter GardinerApotheosis IV, 2023Oil on canvas150 x 120cmSold

Peter GardinerApotheosis IV, 2023Oil on canvas150 x 120cmSold -

John GloverBurning of the Tower of London (AWN:11048), Circa 1820Sepia ink on paper, framed10 x 14.3cm image size

John GloverBurning of the Tower of London (AWN:11048), Circa 1820Sepia ink on paper, framed10 x 14.3cm image size -

John GloverLondon in a Fog, Circa 1820Sepia ink on paper, framed9.6 x 14.9cm image size

John GloverLondon in a Fog, Circa 1820Sepia ink on paper, framed9.6 x 14.9cm image size -

Tony MighellFly Fishing on Saltwater Creek B, 2021Ink on paper, framed47 x 50.5cm, framedSold

Tony MighellFly Fishing on Saltwater Creek B, 2021Ink on paper, framed47 x 50.5cm, framedSold -

Kayi Kayi NampitjinpaUntitled, 2010Acrylic on linen181 x 244cmSold

Kayi Kayi NampitjinpaUntitled, 2010Acrylic on linen181 x 244cmSold -

Nyurapayia NampitjinpaPunkilpirri, 2009Acrylic on linen182 x 244cmSold

Nyurapayia NampitjinpaPunkilpirri, 2009Acrylic on linen182 x 244cmSold -

Wentja Morgan NapaltjarriRockholes West of Kintore AEWMN10-08222PAG, 2008Acrylic on linen200 x 500cmSold

Wentja Morgan NapaltjarriRockholes West of Kintore AEWMN10-08222PAG, 2008Acrylic on linen200 x 500cmSold -

Kirsty NeilsonFern gully, 2023Oil on polycotton78.5 x 63.5cmSold

Kirsty NeilsonFern gully, 2023Oil on polycotton78.5 x 63.5cmSold -

Jorna NewberryNigintaka Perentie, Nigintaka Perentie (JNKM2012023), 2022Acrylic on linen200 x 300cmSold

Jorna NewberryNigintaka Perentie, Nigintaka Perentie (JNKM2012023), 2022Acrylic on linen200 x 300cmSold -

-

Naata NungurrayiUntitled, 2012Acrylic on linen181 x 244cmSold

Naata NungurrayiUntitled, 2012Acrylic on linen181 x 244cmSold -

-

-

Paul RyanBackwash, 2023Oil stick on cotton rag paper, framed35.5 x 24.5cm, paper sizeSold

Paul RyanBackwash, 2023Oil stick on cotton rag paper, framed35.5 x 24.5cm, paper sizeSold -

Paul RyanSkull and Camp Fire, 2023Oil stick on cotton rag paper, framed35.5 x 24.5cm, paper sizeSold

Paul RyanSkull and Camp Fire, 2023Oil stick on cotton rag paper, framed35.5 x 24.5cm, paper sizeSold -

-

Caroline ZilinskyThargomindah (Almost Home), 2023Oil on linen97 x 87cmSold

Caroline ZilinskyThargomindah (Almost Home), 2023Oil on linen97 x 87cmSold

-